Shelby was born with Neurofibromatosis (NF), a genetic disorder that causes tumours to form in her brain. Her condition has meant that her life so far has been an uphill battle filled with countless medical specialists, interventions, tests, MRI's and surgeries. Recently, Shelby was confronted with a life-threatening brain tumour that saw her contemplating life and death; discussing funeral arrangements and coffin designs as though it were a normal part of adolescence.

Shelby was born with Neurofibromatosis (NF), a genetic disorder that causes tumours to form in her brain. Her condition has meant that her life so far has been an uphill battle filled with countless medical specialists, interventions, tests, MRI's and surgeries. Recently, Shelby was confronted with a life-threatening brain tumour that saw her contemplating life and death; discussing funeral arrangements and coffin designs as though it were a normal part of adolescence.

This is Shelby's story and this is the reality of living with NF.

When Shelby was born, her mum Kirsty was in absolute awe as to how beautiful and utterly perfect she was. Kirsty knew about Neurofibromatosis, as Shelby's father suffered from the condition, but when she spotted a little brown birthmark on her newborn's leg, her heart sank. She knew that café-au-lait spots were a marker for NF1.

Despite telling herself that her baby would be healthy, Kirsty instantly knew, that Shelby had NF. Rather than panic, Kirsty shut the fear down and assured herself that it was just a "birthmark"... after all, so many children are born with them and they are harmless. This mark on Shelby didn't have to mean anything...right?

For a long time, it was easy to live in a bubble of denial and enjoy her precious little girl. It was surprisingly easy to refuse to accept a diagnosis of NF1 or think about how it might impact her daughter's life. "It is just a birthmark", Kirsty would say to reassure herself. But as more and more spots started to appear over Shelby's body it became impossible to deny the truth and impossible to imagine what would soon follow.

Accepting the diagnosis of a genetic disease is both heartbreaking and terrifying for a mother whose only wish is for their child to be happy and healthy. There is a period of grieving; a sense of hopelessness that must be overcome before finding the strength to confront each fear head-on.

Accepting the diagnosis of a genetic disease is both heartbreaking and terrifying for a mother whose only wish is for their child to be happy and healthy. There is a period of grieving; a sense of hopelessness that must be overcome before finding the strength to confront each fear head-on.

Questions flooded Kirsty's every thought..."Will Shelby develop tumours?", "is she going to struggle to learn?", "will she develop lumps all over her skin?", "is she at a higher risk of cancer?".

However, for Kirsty, the first few years of Shelby's life were uneventful and dare she say it, "normal". The fear surrounding NF began to dissipate and before too long Kirsty just assumed that Shelby would only be mildly impacted, and NF would not haunt her family further.

It was easy to dismiss Shelby's struggle to achieve milestones because every child develops differently. When Shelby had difficulty with processing words and working out their meaning, Kirsty used flashcards and they developed their own way of communicating. It was only when Shelby started school that it became clear that she wasn't like all of the other children her age.

School was difficult. The noise of the classroom was overwhelming, and the workload was challenging. All of a sudden Kirsty was attending meetings with teachers and psychologists, who all noted that Shelby was significantly behind. To them, the answer was simple - more work needed to be done at home and more outside appointments needed to be made. And so, that is what they did.

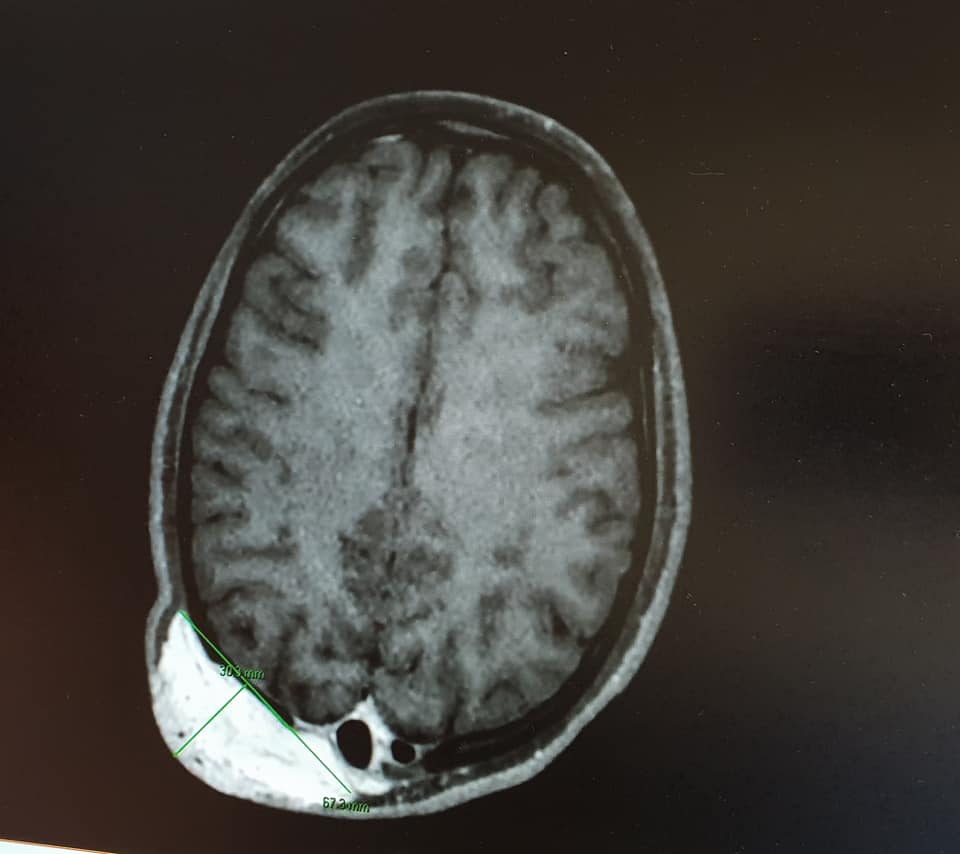

When Shelby was six years old, Kirsty noticed an unusual dent on her head. After numerous specialists dismissed Kirsty's concerns, a neurologist finally ordered an MRI. "It was horrific watching them strap her to the table. She was screaming as the machine was so loud, and it was all intensified by her sensory processing disorder", Kirsty explained. The results were inconclusive, so Kirsty assumed Shelby was fine.

Fast forward two years, Kirsty started to notice the size of the area on Shelby's head that appeared concaved and abnormal had increased - she was rushed in for a head X-ray. Within minutes she was told that Shelby had a 3cm bony lesion on her skull and urgent follow up was needed.

It was then that Kirsty was informed that Shelby's skull had started eating itself away and that there was nothing protecting her brain except for soft tissue. Despite being told that a bump to her daughter's head could result in a life-threatening injury, Kirsty and Shelby were sent home. They were told that surgery was not an option as the risk was "too high" to the main drainage vein of her brain.

For years Shelby lived in pain and was reminded constantly by specialists that her prognosis was not good. She felt like a number on a form; a patient and not a person who was at real risk of dying.

"I remember walking out of an appointment with Shelby and there was a little girl in the waiting room with no legs. Shelby was 8 and said, "she can have my legs mum, I'm not going to need them anymore". It was as though she accepted that her time here with me and her family was finite and all I could do was cry because deep down, I felt like she was right."

Kirsty

Shelby's Mum

It was in 2016, that things went from bad to worse. A tumour was discovered next to the hole in Shelby's skull. It was a plexiform neurofibroma, a type of tumour that does not respond effectively to chemotherapy nor can it be easily removed with surgery.

It was in 2016, that things went from bad to worse. A tumour was discovered next to the hole in Shelby's skull. It was a plexiform neurofibroma, a type of tumour that does not respond effectively to chemotherapy nor can it be easily removed with surgery.

It wasn't until this year, 2020, amidst a global pandemic and bushfires, that Kirsty found a neurosurgeon willing to operate on Shelby and debulk her tumour. Life in their household was thrown into utter chaos. Kirsty and her family were told to prepare for the very real possibility that Shelby could have a stroke and die on the operating table or be left in a vegetative state. Kirsty tried to remain positive and refused to say goodbye, as though somehow, it would ensure Shelby survived. But she was terrified.

Shelby had already told her mum exactly what she wanted at her funeral and had even brought up the colour of the coffin she would like. No child should have to live with tumours as their normal, let alone be confronted with the possibility of death.

COVID-19 meant that Kirsty had to take Shelby to the hospital and wait for hours while she underwent brain surgery, alone. If Shelby was brave enough to lay on the table and wait to be wheeled into the operating room to confront her mortality, Kirsty decided she was brave enough to wait, alone with her thoughts and fears, for however long the surgery took.

The surgery took over four hours. The wait was agonising but worth it. The neurosurgeon was able to successfully debulk Shelby's tumour and place a titanium plate over the 5cm hole in her skull. This result was beyond what they could have hoped for. And despite not being able to remove the entire tumour and being told that it will likely grow back - this was miraculous. More importantly, Shelby was awake and smiling.

On that day, hearing Shelby say "I love you mum", was everything to Kirsty. She stood in awe of her smiling and beautiful daughter, alive and well underneath the tubes, wires, bandages and staples.

During all of this, this formidable mother and daughter dedicated themselves to fundraising for a drug trial that has shown proven success in shrinking and stabilising the size of plexiform neurofibromas.

So far, they have raised over $11,000 for the Children’s Tumour Foundation, a sum that will be invested into the funding of critical drug trials. It gave them both a purpose and something positive to focus on during an incredibly difficult time. In some way, Kirsty believes that it gave Shelby the will to pull through the surgery and speed up her recovery.

Shelby personally wrote to the Prime Minister, local members, and politicians from every party to encourage them to advocate for people living with NF; begging them to assist with the funding of these important trials. In June 2020, the Federal Government announced a commitment to partial funding of the same TiNT MEK Inhibitor trial. The first-ever government-funded NF Research.

Shelby’s battles leave us all in awe of her resilience, courage and determination. We are inspired by her advocacy efforts as she teaches those around her that every person is able to make an impact and pave the way for change.